How digital platforms reform traditional purchasing processes at retailers and sales strategies at brands and manufacturers.

How digital platforms reform traditional purchasing processes at retailers and sales strategies at brands and manufacturers.

Extensions of product ranges and offers in the form of marketplaces or supplier platforms are booming. Just recently, Amazon has reported a record turnover of 2.8 billion for the Amazon Marketplace – big online shops such as Otto, Lidl or Real extended their bricks-and-mortar shops into the age of e-commerce long ago and have developed so-called partner platforms. The difference to an open marketplace is usually: Suppliers don’t compete for prices and are invisible for end-consumers – customer service and invoicing is managed by the platform itself.

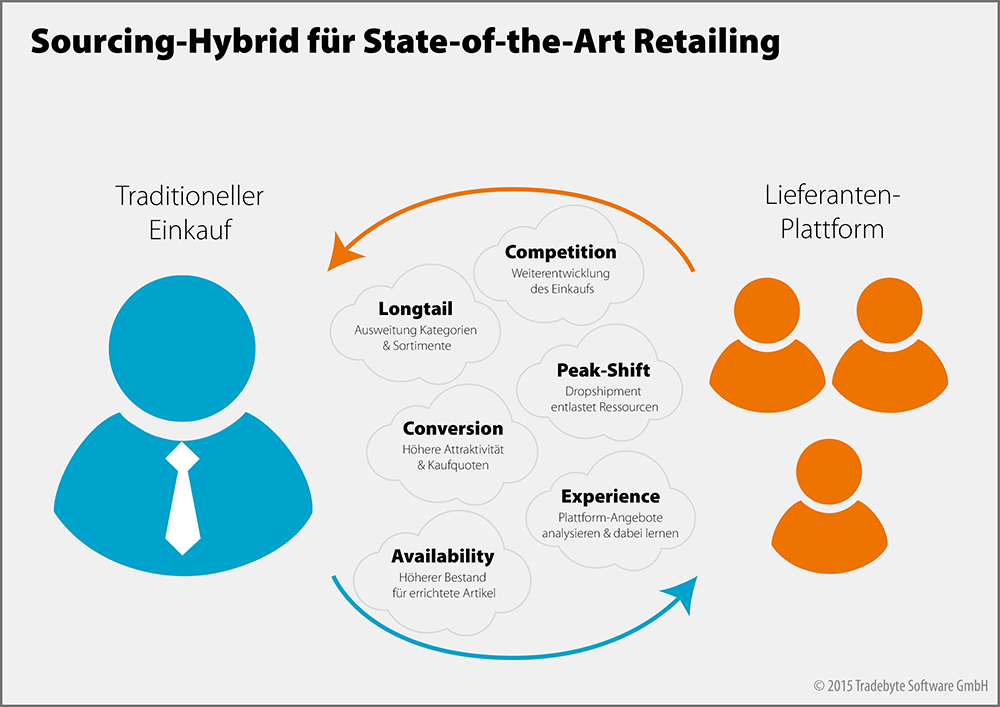

However, the combination of traditional purchasing and the connected product range of partners doesn‘t come from the online industry. After all, successful bricks-and-mortar retailers can look back on a long history of established concepts for effective floor management. Here, responsibility is transferred to connected manufacturers and brands. Quite often, the partner takes responsibility for the product selection in their own “brand area” and the stock and price setting, instead of the retailer himself. That increases motivation and provides relief to the retailer, not only for the risk of devaluation. So, the classic purchasing principle, which saw risks and responsibility mainly with the trader, has already developed into something new.

Wholesale is past – hybrid models are the future

The digital transition promoted by modern e-commerce is now taking this success story to online commerce. Modern manufacturers have long had the infrastructure to allow them to deliver article data, content, inventory and prices to the retail customer and to even send the order directly to the end-consumer. A vendor can therefore be present via many sales channels and centrally access a storage location, which considerable reduces inventory risks. Furthermore, it gives him full control over prices and he can present his entire product range to the end-consumer – selective purchasing processes are a thing of the past and the classic wholesale model is gradually supplemented or even replaced.

From the point-of-view of the retailer, a platform also creates entirely new opportunities. On the one hand, he can fill already created articles with more stock. On the other hand, he can display a much bigger product and brand diversity (long tail) than would be possible with traditional purchasing which leads to him drawing conclusions for his own purchasing strategy. The productive competition between purchasing and platform has already led to a quiet revolution of their purchasing behaviour with some retailers, and has unlocked unimagined synergies.

In order to guarantee a consistent customer experience despite the external product range, supplier agreements are often supplemented with so-called SLA appendices, in which fundamentals – such as delivery times or reaction times to customer enquiries – are stated. These SLA specifications are monitored via special tools and regularly discussed. Often the end-consumer is not aware that the supply and delivery come from an external supplier – what remains is a positive shopping experience.

After all, a bigger selection means more conversions and a higher shopping basket value, the bounce rate is minimised. Offers for cross-selling reach a new dimension and neglected categories are suddenly filled by experts close to the market (namely suppliers).

Naturally, this additional turnover does not come about without additional effort. In comparison to classic resources for purchasing, product management, storage, as well as commodity risks and capital accumulation, the effort for a supplier platform is more than manageable. The hybrid of purchasing and platform is therefore a classic win-win-situation where manufacturers, vendors and retailers can profit equally. And there‘s another “win”: the end-consumer is also overjoyed. Because there‘s only one vendor, one shopping basket and one payment process.

Back to main Blog

Back to main Blog